The KLF: When Music Could Still Set The World On Fire

The smell of burning money still lingers in the air of British music history. One million pounds, to be exact.

In an era when we worry about losing our Spotify playlists, it's almost impossible to imagine artists taking their master tapes to a remote Scottish island and literally burning their entire back catalog. But that's exactly what The KLF did, and it perfectly encapsulates why the late 80s and early 90s held a kind of magic we might never see again.

I first encountered The KLF through a crackling radio broadcast of "3 AM Eternal" in 1991. Back then, radio wasn't an algorithm-driven playlist - it was a gateway to musical mysteries. The KLF, helmed by Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty, embodied that sense of mystery. They emerged from the underground scenes of Liverpool and London, carrying with them the raw energy of an era when creating electronic music meant getting your hands dirty with actual hardware.

The story of The KLF begins like many great tales from the 80s - with a borrowed car and a crazy idea. In 1987, Bill Drummond sat in a tiny flat in South London, reflecting on his past life as a music industry insider. Approaching 33 1/3 years old (the exact speed of a vinyl LP), he felt an urge to dive back into music, but this time on his own anarchic terms. A chance meeting with Jimmy Cauty, a young guitarist who shared his distaste for music industry conventions, sparked something electric. Operating from Cauty's squat in Stockwell, they started experimenting with hip-hop under the name The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu (The JAMs). Their setup was beautifully primitive - just a borrowed sampler, some vinyl records, and two minds buzzing with the possibility of creating chaos in the charts. Early recording sessions involved literally stealing samples from ABBA records, daring the industry to come after them. And come they did - but each cease-and-desist letter only fueled their creative fire. This wasn't about careful career planning or building a social media following - it was about two guys in a room, armed with nothing but audacity and a determination to turn the music industry upside down.

The process of making their music takes me back to those days of physical media. While today's producers craft beats on pristine digital workstations, Drummond and Cauty were literally splicing tape, sampling vinyl, and building sounds from the ground up. They worked with what they had, turning limitations into artistic statements. Their studio wasn't a MacBook Pro with Logic - it was a real space filled with synthesizers, drum machines, and miles of cable.

Their rise to becoming 1991's highest-selling singles band reads like a story from another dimension. Here were two guys who started by making hip-hop under the name The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu (The JAMs), sampling everything from ABBA to the Doctor Who theme, daring the music industry to sue them. And sue they did. But instead of backing down, The KLF turned each legal battle into performance art.

The beauty of their music lay in its ability to exist in multiple worlds simultaneously. "What Time Is Love?" could be heard blasting from a Ford Escort's stereo on a Friday night cruise through town, while their ambient album "Chill Out" became the soundtrack for late-night sessions in bedrooms across the country. This was a cultural phenomenon that connected the mainstream with the underground.

How The KLF Turned Chaos into Art

Imagine walking into a bookstore in 1988, browsing the music section, and finding a book that promised to teach you how to create a number one hit - without any musical talent. That book, "The Manual (How to Have a Number One the Easy Way)," sat on shelves as a testament to The KLF's beautiful audacity. They wrote it after literally scoring a hit with "Doctorin' the Tardis," a track cobbled together from samples of the Doctor Who theme and Gary Glitter's "Rock and Roll (Part Two)." The book wasn't some dry industry guide - it read like a manifesto for creative chaos, teaching readers how to game a system that took itself far too seriously.

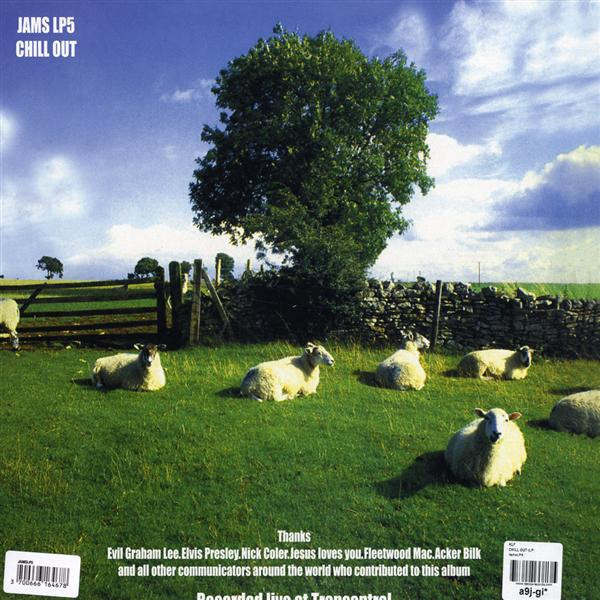

But while "The Manual" showed their satirical side, their album "Chill Out" revealed something deeper. Released in February 1990, it captured a moment when electronic music could still feel like a mysterious transmission from another world. The album takes listeners on a dreamy journey through America's Gulf Coast states, from Texas to Louisiana, but not the real America - this was the America of late-night TV shows, crackling radio signals, and half-remembered dreams.

I remember first hearing "Chill Out" on a borrowed cassette, laying in the dark with headphones on. The album flowed like one continuous piece, mixing in sounds that shouldn't work together but somehow did - Elvis's voice, train whistles, nature sounds, and snippets of country music all woven into an ambient tapestry. This wasn't music made with careful market research - it was pure creative exploration, the kind that could only happen when artists followed their instincts instead of social media metrics.

The cover art showed sheep grazing in a serene landscape - a strangely peaceful image for a band known for their anarchic stunts. Yet it perfectly captured the album's essence. While other electronic artists chased the latest trends, The KLF created something timeless. They coined the term 'ambient house' almost by accident, spawning an entire genre through pure experimentation.

The band's influence echoed through literature as well. "2023: A Trilogy" emerged as a strange piece of dystopian fiction that defied categorization - much like the band itself. Writers and cultural figures from Alan Moore to Terry Gilliam found themselves drawn into The KLF's orbit, recognizing that this wasn't only about music anymore. It was about challenging every creative boundary they could find.

In an era when artists carefully curate their output, The KLF's creative approach feels almost alien. They followed their ideas down whatever rabbit holes appeared, whether that meant writing a satirical manual, creating an ambient masterpiece, or penning dystopian fiction. Each project carried that distinct KLF spirit - a mix of serious artistic ambition and playful absurdity that could only have emerged in an age when creative freedom meant something different than it does today.

Their performances defied everything we've come to expect from modern, sanitized music industry events. Take their infamous 1992 Brit Awards appearance - no carefully choreographed dance routines or lip-synced perfection here. Instead, they collaborated with grindcore band Extreme Noise Terror to perform a metal version of "3 AM Eternal," fired blanks from a machine gun into the audience, and left a dead sheep at the afterparty with the message "I died for ewe." Try imagining that at today's BRIT Awards.

The way they handled money feels almost alien in today's careful, brand-conscious music industry. After hitting the top of the charts multiple times, they didn't invest in stocks or start a clothing line - they burned a million pounds on that Scottish island. When asked why, they signed a contract agreeing not to explain their actions for 23 years. In an age of instant explanations and carefully crafted social media apologies, such commitment to mystery feels revolutionary.

Their Ice Cream Van period perfectly captures the era's wonderful weirdness. Picture this: one of the biggest bands in the country, touring Scotland in an ice cream van, playing their hits through its tinny speakers. No social media announcement, no livestream - if you weren't there, you missed it. That's how music used to work. Events existed in the moment, becoming legendary through word of mouth rather than Instagram Stories.

The KLF's disappearance in 1994 marked the end of an era. They didn't fade away with a series of diminishing returns or carefully planned farewell tours. They simply stopped, deleted their back catalog, and vanished. Nowadays, where constant content creation and endless engagement is king, such a decisive endpoint feels almost impossible to imagine.

Looking back at The KLF from 2025, their story feels like a transmission from a different world - one where music still held secrets, where artists could truly surprise us, and where the biggest band in the country could vanish without a trace. It reminds us of a time when discovering music meant more than clicking a recommendation algorithm, when every new release could potentially change everything, and when the phrase "burning a million pounds" wasn't just a metaphor for a bad investment.

The KLF was about the possibility of magic in an analog world. And sometimes, late at night, when I hear those opening beats of "3 AM Eternal," I can still feel that magic, pulsing through time like a signal from a lost world we might never see again.